An Irish Graduate Student Discovers Pulsars, An English Man gets the Nobel Prize

How a Humble Irish Woman Overcame Injustice to Become the World-Renowned Astronomer who discovered Pulsars

To suffer is to learn humility, true humility.

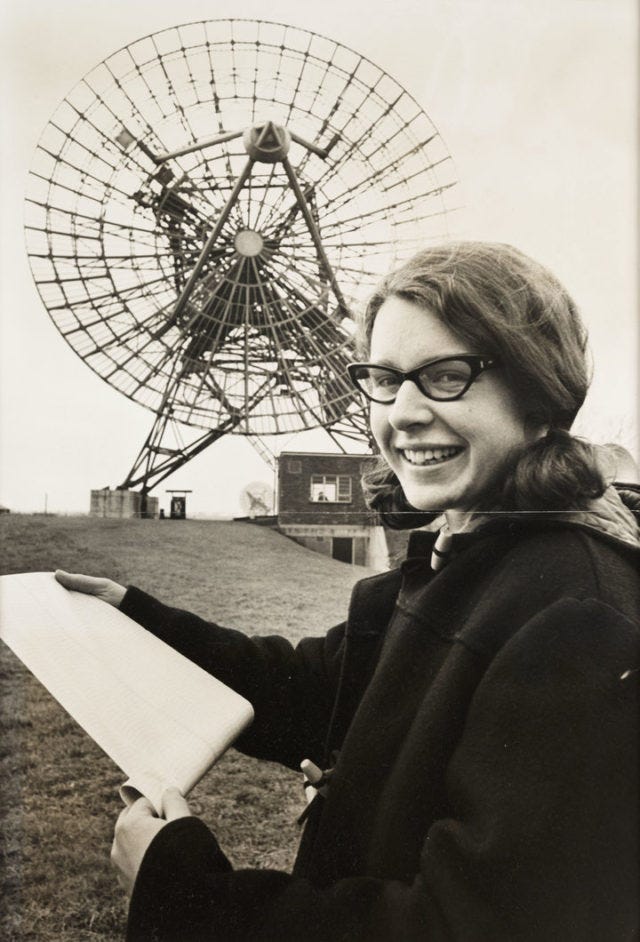

Jocelyn Bell, no doubt, suffered in silence from the insult and the culture that led to it, one of the greatest professional injustices in modern academia. Given my Irish heritage, I have a particular interest in this story and, although the title could be a trigger or flash point for some, that isn't my intention. The above title is simply a statement of fact and is a key aspect of the story that will be told here, the seminal discovery of Pulsars by Susan Jocelyn Bell [Burnell].

I write this article for the following reasons:

Tell the story of how Pulsars were discovered, a term considered a "household word" today in the Astrophysical community;

Address a historically grotesque injustice perpetrated on a humble student who took the moral high road when confronted with the systemic and entrenched sexism in a male-dominated field;

Chronicle another chapter in the long history of injustice perpetrated on the Irish race;

Highlight the contribution of Women in science, specifically Astrophysics.

Growing up In the North of Ireland

The oldest of four children, Susan Jocelyn was born to M. Allison and G. Philip Bell in Belfast, (N) Ireland on July 15, 1943 and grew up in Lurgan, County Armagh.

Being born in Belfast and growing up in a veritable war zone of racism, classism, sectarian violence and state-sponsored terrorism, was part and parcel for Irish people living on their land with a foreign flag flying in that province's Capital city. Although the vitriol was primarily reserved for Catholics, the basic tenets of the Quakers, their gentle manner and quiet nature were, no doubt, unpalatable to the sectarian gangs that patrolled the streets of Belfast and greater Armagh. As a side note, the Republic of Ireland (the 26 counties to the south of the political divide that separates what is known today as "Northern Ireland" from the rest of the island), won its independence from Great Britain only 21 years earlier at the time of her birth in 1943. Three of the primary tenets of the Quaker faith are:

Women are permitted to teach and hold positions

Social hierarchies were to be disregarded and

Pacifism was to be followed;

All these tenets are diametrically opposed to the ingrained Monarchistic, Colonialist and Provincial social order of the day in that part of Europe and, no doubt, gave her the tools to overcome much adversity in the pursuit of her degree and her career.

Set against the generally provincial, conservative establishment of the day -a posture that sought to maintain the status quo in the six counties -by any standard, these three tenets would be considered progressive in the sense understood by such leaders as Franklin Delano Roosevelt. They allowed Jocelyn to excel and thrive in school, specifically in science. When the other girls were in Homemaking, she was in the physics lab.

Beginnings and The Discovery of Pulsars

From her humble beginnings, Dr. Bell-Burnell went on to observe radio emissions from pulsars for the first time in history, making one of the most significant discoveries in astronomy of the 20th century.

Jocelyn's father was an architect by profession and, as serendipity would have it, one of his clients was the Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, just down the road from the family home in Lurgan. Being drawn to science and with a strong family cohesion (a character engendered by the Quaker faith), Jocelyn would spend much of her time as a child with her father -and at the Observatory. Of course she would spend hours and days pouring over the astronomy books and literature and, as her interest in the subject grew, she was encouraged by the staff of the Observatory to pursue a career in astronomy. As can be inferred by now, her father played a central role in her choice of careers and lest his influence be overlooked, he designed the Armagh Planetarium!

As she recalls in a recent interview:

I was about 14 years old when my father brought home an astronomy book from the public library by Fred Hoyle called Frontiers of Astronomy. It was quite a tough read for a 14-year-old, but I took it up to my room and read it from cover to cover — I was hooked.

To get a sense of how difficult it was for a woman to make a name for herself in science in the conservative, male-dominated culture she was immersed in, given the restrictions and societal conventions of the day, she recalls the trajectory of her career at the time:

I got married just as I finished my PhD and had a child fairly soon after that. I then spent about 20 years picking up part-time work in any kind of astronomy, near where my husband was working.

It should be pointed out that in 1969, the year she received her degree, the Irish Civil Rights Movement was moving into high gear, a point in time that would begin a 30-year struggle against sectarian violence and strife known as "The Troubles". This period would culminate with the now famous 1998 Good Friday Agreement between the Irish and British governments that provided a power-sharing framework for the six counties. That framework is now in jeopardy with "BrExit" and the six counties of the North voting to remain in the European Union.

As it turns out, the world famous British Astronomer Fred Hoyle, author of the book she read cover-to-cover as a fourteen-year-old, would come to play a positive role in her career as she progressed.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Astronomy For Change Substack by James Daly, Ph.D to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.